Kenya, a country slightly more then twice the size of Nevada, is known for its diverse wildlife, land safaris, ancient Swahili cities, and the hot, dry climate. Kenya is also the newest location where students use the Leaf Pack Kit.

Kenya, a country slightly more then twice the size of Nevada, is known for its diverse wildlife, land safaris, ancient Swahili cities, and the hot, dry climate. Kenya is also the newest location where students use the Leaf Pack Kit.

In 2002 Professor Wangari Maathai, Nobel Peace Prize nominee and currently deputy minister for the environment in the Kenyan government, visited Stroud Water Research Center to speak at a Joan M. Stroud Memorial Lecture Series.

Dr. Maathai is the founder of the Green Belt Movement (GBM), a grassroots Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) engaged in environmental conservation and community development. For over 26 years, GBM has used tree planting as an entry point to community development with great success: since 1977 GBM volunteers have planted over 20 million trees!

At the end of her visit to the Stroud Center, Prof. Maathai, was given a Leaf Pack Kit with the hope that she could engage students in Kenyan schools in a new and exciting approach to conservation.

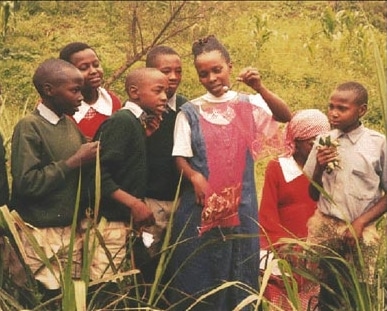

GBM staff, led by Wanjiku Muikia, and Joseph Karangathi, along with help from Wanjira and Muta Mathai (Prof. Maathai’s children), used the Leaf Pack Kit to create a pilot project to educate communities on the importance of streamside trees. “As part of their conservation agenda,” Wanjira told us, “GBM encourages communities to plant indigenous trees to conserve local biodiversity, prevent soil erosion, and enhance natural beauty. The Leaf Pack project has involved a sector of society that would ordinarily not participate in the broader conservation debate – primary school students.” Wanjiku approached the principals of three schools: Kibichiku Primary School on the Mutundu River, Ruthimitu Primary School on the Nyongara River, and Kangemi Primary School on the Nairobi River, and they agreed to have students begin working with the kits.

Weighing the leaf packs, Ruthimitu Primary School

“To make the process participatory,” Wanjira said, “GBM and the schools engaged parents and elders from the community. The elders, who were invited to speak to the students about the history of the rivers, touched on such issues as the size of the river, its cleanliness, and how it has changed over the years. The elders also provided traditional indicators for clear and turbid (cloudy, muddy) streams affected by upstream erosion: clear streams often have water beetles and frogs, while turbid streams often have a mud beetle known locally as wanjiku wa ndoro. Earthworms were mentioned as indicators of both clear and turbid rivers. Parents or other adults then gave each student an assignment to gather information about the various life forms they saw in the river. By involving the entire community from the beginning, the process ensured ownership of the project and established interest in its outcome. It also increased the students’ awareness of the history of the river.”

The Results Are In!

Mutundu River: Healthy

Based on the diversity of macroinvertebrates found, Kibichiku Primary School determined that the Mutundu River is: HEALTHY

Examples of macroinvertebrates students found inthe Mutundu River:

- Craneflies

- Stoneflies

- Dobsonflies

- Caddisflies

- Alderflies

- Aquatic earthworms

Nairobi River: Unhealthy

Based on the lack of diversity of macroinvertebrates found, Kangemi Primary School determined that the Nairobi River is: UNHEALTHY

Examples of macroinvertebrates students found in the Nairobi River:

- True flies

- Damselflies

- Aquatic earthworms

Unfortunately, the third school, Ruthimitu Primary School, lost its leaf packs, which is a common problem when packs are poorly attached to the stream bottom. However, both students and teachers are eager to try the experiment again. The next step is for the students to present their findings to one another and submit their data on the Leaf Pack Network.

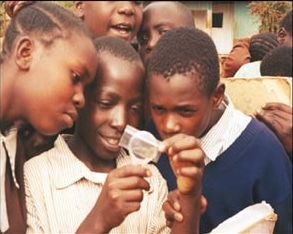

Examining macroinvertebrates from Nairobi River

“By implementing this project through schools,” Wanjira said, “GBM has been able to instill a conservation message through schools, engage students in investigating the role of naturally fallen tree foliage on the ecology of streams, and offer them an interesting and exciting experiment.”

The program had many benefits. The students were inspired to start tree nurseries to reclaim the riparian area, and they learned firsthand why they should not drink unboiled water directly from the river.

In Kibichiku Primary School, for example, the students experimented on the Mutundu River, which is named for an indigenous tree (Croton macrostachyus). After the elders had explained to the students that the river carries the name because the trees flourished there, the students noted not a single Mutundu tree stood along the riparian area. That inspired them to restore the original Mutundu River by starting a riparian replanting project.

In its report, GBM states that, “In the next phase GBM plans to engage various sectors of the government and NGOs background information and data on the streams involved in this and future studies.” The Stroud Center will also help GBM get in touch with scientists who have done research on Kenyan streams. The work of the Kenyan students will surely inspire students of all ages around the world to make a difference in their watersheds!

For additional information about this project or Leaf Pack Network, contact the Leaf Pack Network administrator.

References:

- BBC WorldService.com: Urban Water Solutions

- Nairobi: History

- The Green Belt Movement

- Lonely Planet: Destinations

- United Nations Environment Program Nairobi River Basin Project Photo Gallery

- WorldAtlas.com